By: Rajat Anilkumar

I am a global health researcher with an interest in maternal and newborn health. I came across the topic of Indigenous midwifery while exploring the role of midwives in remote settings. I was fascinated by their unique role in their community in improving maternal and newborn health. The more I read about them, the more I became interested, specifically in their role of preserving and protecting each woman’s cultural traditions and identities in their communities. However, what really drew me to their story was the depth of history and resilience behind their practices. For centuries, Indigenous midwives have been central figures in their communities, ensuring the physical, mental, emotional and spiritual well-being of pregnant women and their families. With the advent of colonisation, Indigenous midwifery was restricted, criminalised and slowly erased. Their practice of traditional knowledge and culture was deemed unsafe and inferior. Despite the attempts of the colonial powers, the Indigenous midwifery community resisted, and today there is a resurgence within the community to reclaim autonomy and restore traditional knowledge and practice. This piece is my way of acknowledging their unique role, recognising their historical and ongoing fight and advocating for their rightful and distinct space within maternal and newborn healthcare.

So, who are Indigenous midwives and what is their story?

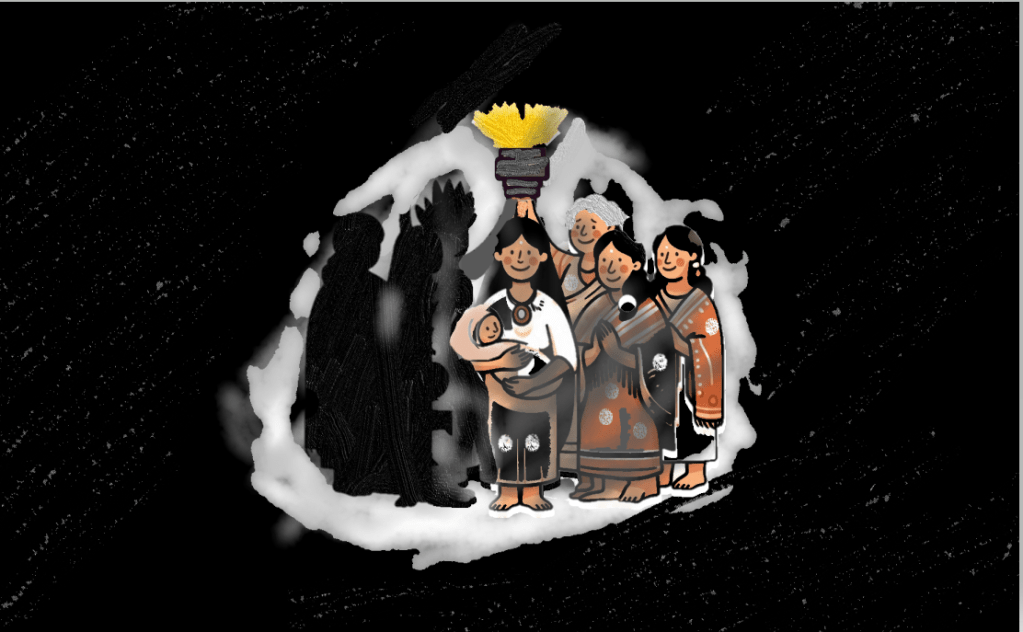

Indigenous midwives are Indigenous people who provide comprehensive care for pregnant women, newborns and their families. Beyond clinical care, their role extends to promoting breastfeeding, nutrition and parenting skills, contributing to the long-term well-being of individuals and communities (2,8). Indigenous midwives emphasise shared decision-making, ensuring women are actively involved in their care and respected as key decision-makers. The use of Indigenous language by midwives reinforces this approach, allowing women to express their needs and make informed choices more easily (8). What stands out to me is how Indigenous midwives play a crucial role in safeguarding and supporting women’s cultural traditions during pregnancy and birth. This can include drawing on traditional birthing knowledge passed down through generations, incorporating practices such as singing during labour, and involving elders or family members in the care process. These practices make care feel more respectful, familiar, and connected to the community

In many Indigenous communities, birth is viewed as sacred, and, in some traditions, each newborn is believed to have a deep connection to the earth. This connection is reflected in ceremonies that honour both the newborn and their bond with the land. One example I came across is the Māori tradition of burying the placenta, known as whenua, on ancestral land. The word whenua also means land, symbolising the deep relationship between the newborn, their ancestors, and the land they come from. This understanding of birth as interwoven with ancestry and nature stands in sharp contrast to Western biomedical models, which often focus solely on the biological aspects of birth.

Research shows that Indigenous midwifery improves maternal and newborn health by providing culturally safe care. This approach encourages early prenatal visits, reduces preterm births, and increases breastfeeding rates (2). Indigenous midwives also help lower medical intervention rates by focusing on natural birth practices and minimising unnecessary procedures, such as cesarean sections (8). Furthermore, they build trust with expectant mothers and their families by offering care that respects cultural traditions. This trust leads to better communication, increasing the likelihood that women will seek timely care and follow health advice (3).

Despite the cultural and health significance of the Indigenous midwifery model of care, colonial powers sought to dismantle it to control women and impose Western models systematically. Midwives, once central to the birthing process, were framed as uneducated and incompetent in providing care. The result was a shift towards institutionalised birth, where Indigenous women were forcibly evacuated to give birth in hospitals, often far from home, without family or community support. Traditional practices such as the use of abdominal massage to ease the pain were dismissed. This separation stripped the newborns of their connection to their culture, distancing them from the practices that shape their identity. It is interesting to note that these policies were justified under the guise of improving maternal and newborn health outcomes (11). However, reality tells a different story. A story of displacement, harm and the long-lasting consequences of policies that prioritised control over care.

Evidence shows that forced separation of women from midwives, their families and communities created emotional distress, contributing to higher rates of anxiety and adverse birth outcomes such as preterm labour and low birth weight (4). Systemic racism and discrimination within maternal healthcare further exacerbated these outcomes, with women often facing neglect and mistreatment. These factors resulted in significant disparities in maternal health outcomes, as evidenced by the fact that Indigenous people of the United States are twice as likely to die from pregnancy-related causes compared to non-Indigenous women. (5).

Despite the attempts to erase Indigenous knowledge, midwives and their communities have long withstood the generations of oppression, reflecting their resilience. Today, a growing movement within Indigenous communities is driving the resurgence of Indigenous midwifery, reclaiming traditional practices and autonomy. One such effort is the establishment of Indigenous-led birthing centres, such as Inuulitsivik Maternity in Puvirnituq, Nunavik, which opened in 1986 (6). Since then, the centre has welcomed over 3,000 births, with cesarean rates as low as 2%—a stark contrast to Canada’s national average of nearly 32% in 2021-22 (7). Its perinatal mortality rates remain under 1%, aligning with national figures (7).

However, the progress has been slow and significant challenges remain globally. Indigenous midwifery continues to face systemic barriers due to a lack of formal recognition, funding, and shortages of resources and workforce (e.g. Aboriginal midwives represent 2% of Australia’s midwifery workforce) (8). In Canada, Inuit midwifery remained unregulated until the 1990s, reflecting the slow recognition of its legitimacy despite its longstanding role in community care. Pregnant women continue to be forcibly taken to hospitals, undermining midwifery practice (9). However, recent progress signals a growing acknowledgement of Indigenous midwifery. In March 2024, the Mexican Congress recognised approximately 15,400 traditional midwives and granted them the authority to issue birth certificates (10).

Why do these narratives on Indigenous midwives matter, and how can we support them in the current global health landscape?

As we have seen in the narrative above, Indigenous midwives are essential in ensuring a positive birthing experience and improving maternal and newborn health outcomes. Beyond disparities in care, the long history of discrimination, exclusion and medical experimentation has led to widespread intergenerational trauma and deep-seated mistrust in healthcare systems in the community. Indigenous midwifery can be a path forward to healing the harm inflicted on Indigenous communities, as they provide care rooted in trust and cultural traditions.

With global health challenges like climate change intensifying, I believe these communities are disproportionately affected, particularly in maternal and newborn health. For example, many Indigenous populations already live in climate-vulnerable regions, where access to healthcare is limited. The increasing impacts of climate change, such as extreme weather, only worsen these existing challenges, making it even harder for mothers and newborns to get the care they need. In the context of these compounded challenges, Indigenous midwifery plays a crucial role in restoring trust and providing culturally grounded care. It offers a resilient path forward for improving maternal and newborn health in communities too often overlooked.

Supporting Indigenous midwifery amid global health challenges requires systemic change and direct investment. In my opinion, strengthening maternity care centres through improved infrastructure and resources, expanding midwifery education, and granting midwives autonomy are essential steps. Additionally, I believe cultural sensitisation among other healthcare professionals is necessary as it can help foster collaboration and reduce systemic biases that undermine Indigenous care models. Finally, it is important to acknowledge colonial legacies, take accountability and concrete steps through legal protections for lasting change.

In retrospect, penning down thoughts for this article has made me realise how power structures determine whose knowledge is valued and whose is disregarded. Indigenous midwives, despite their deep-rooted history within the community, have been sidelined in favour of Western biomedical models. Yet, the resistance and resurgence in reclaiming knowledge and autonomy are also a powerful reminder of the enduring strength of Indigenous midwives and their communities. Moving forward, empowering Indigenous midwifery is a necessary step toward justice, healing, and reclaiming autonomy.

References

3. Sarmiento I, Zuluaga G, Paredes-Solís S, Chomat AM, Loutfi D, Cockcroft A, et al. Bridging Western and Indigenous knowledge through intercultural dialogue: lessons from participatory research in Mexico. BMJ Glob Health [Internet]. 2020 Sep 29 [cited 2025 Apr 20];5(9). Available from: https://gh.bmj.com/content/5/9/e002488

10. NACLA [Internet]. [cited 2024 Sep 30]. Delivering the Future: Midwives Win Breakthrough in Mexico. Available from: https://nacla.org/delivering-future-midwives-win-breakthrough-mexico

11. Silver H, Sarmiento I, Pimentel JP, Budgell R, Cockcroft A, Vang ZM, et al. Childbirth evacuation among rural and remote Indigenous communities in Canada: A scoping review. Women and Birth. 2022 Feb 1;35(1):11–22.

Leave a comment